By HEDY EPSTEIN

Abstract

This paper reports the manipulation of the housing market in St. Louis, Mo. by members of the real estate community. Thirteen (13) black and white checkers visited fifteen (15) white real estate companies for purposes of purchasing or selling a home.

Blatant and subtle methods and techniques of manipulation and discrimination against blacks and whites are described in the report.

The result of this manipulation is the containment of blacks in areas designated by the white real estate community.

I. Introduction

The population distribution in the metropolitan St. Louis area is a study in contrasts. The core city’s population with every passing day increasingly becomes more black, losing at the same time more of its white members to all white enclaves in the suburbs. A quick glance at the St. Louis metropolitan area might give the appearance that the population distribution is a result of a choice of the individuals involved. But not so. For over a year and a half now, fair housing has been the law of the land. Not only has the general public not yet grasped the significance of this fact, but more importantly, this fact has not been put into practice by members of the real estate community.

Racial manipulation of St. Louis housing patterns by real estate dealers was widespread prior to the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Law and the June 1968 Jones vs Alfred H. Mayer Co. U.S. Supreme Court Decision and has continued since that time. Both white and black home buyers, sellers, and renters were and have continued to be victimized. (The Jones vs. Alfred H. Mayer Co. U.S. Supreme Court Decision ruled that discrimination in the sale or rental of all housing is illegal under the Civil Rights Act of 1866. The Civil Rights Law of 1966 also outlaws most such discrimination.)

II. Description of Project: “Patterns of Discrimination”

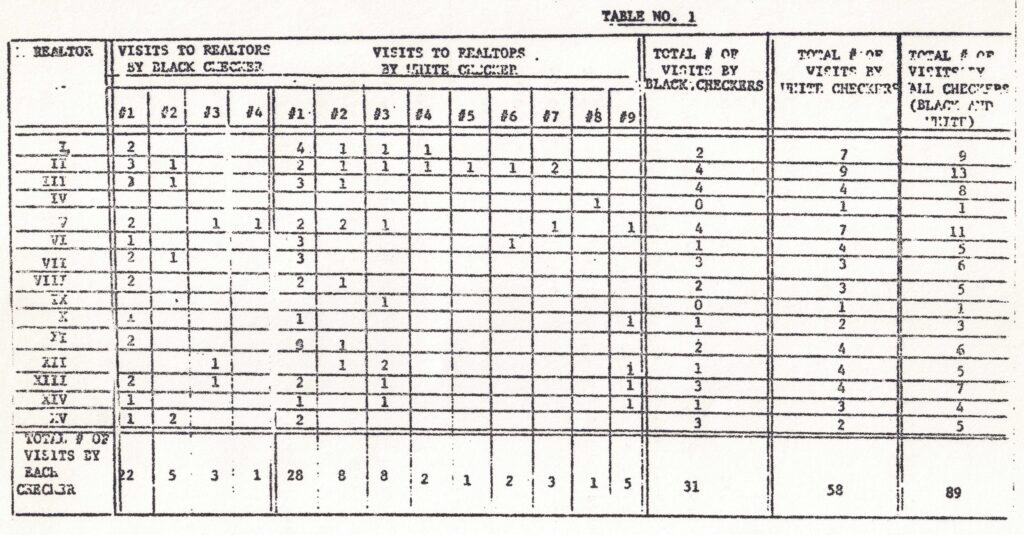

Freedom of Residence receives an average of three complaints of racial discrimination in housing per day. This represents only a fraction of the overall picture of discrimination. Inspired (or better said) “depressed” by this knowledge, Freedom of Residence set out to investigate the “Patterns of Discrimination” as put into operation by the white real estate community. The project began in May, 1969 and lasted about eight months. The material collected reveals the discriminatory practices of white real estate companies in attempting to show blacks only property in all black or integrated areas, and avoiding showing them properties in all white areas. The whites were referred only to properties in all white areas. All black or integrated areas were not mentioned to the white prospective customers. When these whites asked about properties in integrated areas, or about an integrated area in general, they were discouraged or urged not to consider such areas. For purposes of this project thirteen (13) black and white checkers presented themselves as prospective clients to fifteen (15) white real estate companies, sometimes to buy a home, at other times to sell a home. In all, a total of eighty-nine (89) visits were made. (See Table No. 1) When a real estate company had more than one office, the branch offices were also visited. While we were prepared to find widespread violations of the civil rights laws, we were amazed at how easy it was to compile the evidence. In many cases realtors volunteered information and methods to avoid compliance with civil rights laws with no prompting from checkers.

III. Observations and Findings of the Investigation Obtained by Checkers

The statement by white checkers “I’m concerned about my neighborhood” was universally interpreted by realtors as a reference to race. Instead of inquiring what the concern for the neighborhood was, realtors universally replied, “You mean colored,” and then went ahead to tell of their techniques for keeping blacks out of white neighborhoods and steering whites away from all black or integrated neighborhoods.

Despite repeatedly expressed wishes of black checkers that “I don’t wish to live in this (integrated) area,” these black checkers were over and over again referred only to properties in these areas they expressed no interest in. In addition, these black checkers were told by the realtors “these are the only listings we have at this time.” It should be noted here that the realtors visited, all had access to multiple listing service, which lists properties for sale by realtors who subscribe to this service. Some of the realtors visited also had access to a computer listing service. A random check by Freedom of Residence of the multiple listing service and the computer listing indicated that at the same time both white and black checkers visited the real estate companies the particular real estate company visited had their own listings of houses which they did not share with the

(a) black checker apparently because the homes were located in white areas

(b) white checker apparently because the homes were located in integrated areas.

This random check also indicated that homes listed by other realtors also were not shared. We assume the reason was the same as above.

To illustrate the aforementioned, we relate some excerpts from conversations by black and white checkers and the realtors visited by them.

A black checker visited Real Estate Company “A” for the purpose of purchasing a 3 bedroom $25 – 30,000 house. The agent immediately suggested University City (an integrated area.) The checker indicated that she was not particularly interested in University City. The agent countered this with “There are some lovely homes in that area.” The checker repeated that she was not interested in this area and listed seven (7) areas she would like to live in. To this the agent responded:

“Well, we don’t have anything just now.”

A white checker visited the same real estate company about two weeks later also for the purpose of purchasing a home, a 3 bedroom $18 – 22,000 home. The checker specified a geographical area of interest. Included in this area was University City, an integrated area though not specifically mentioned by name. The agent at first suggested four (4) areas well outside the area described by the checker, two (2) of them considerably south, and two (2) of them west. It should be noted here that one of the communities within the boundaries described by this checker has homes that are above the price range indicated. University City has homes in that price range. Near the agent’s desk was a bulletin board with some listings. One of them was a home in University City (integrated area) for $21,900. When the checker inquired about it, the agent said, “It’s a lovely house, but there are colored next door. And wouldn’t you know it they have the biggest house on the block. I know you wouldn’t want to live next door to colored.” When the checker said “I had never given this any thought” the agent said: “Take my advice, you would not want to.” The checker then asked about other University City listings. Reluctantly the agent looked through a couple of pages of University City listings, pointing to one or two and then adding: “These are no good, the houses are too old (Note: Checker had never indicated age of home interested in) and the area is not nice.” With that the agent shut the book and suggested another white suburb. This one, too, was outside of the area of interest expressed by the checker.

About two and a half months later the same white checker visited the same real estate company again. This time it was for the purpose of listing a home for sale. On this occasion the checker spoke to the president of the company, who at that time also was president of the Metropolitan St. Louis Real Estate Board. After the checker had answered some questions about the house to be sold, she mentioned that she was “concerned about her neighborhood.” This was understood to mean “you don’t want to sell your house to colored.” The president of the company then launched into an hour and a half long discourse espousing his views on integration, prejudice and what he called “social do-gooders.” He admitted to being prejudiced, in fact, “since watching TV and reading all about the terrible violence and lack of regard for law and order of the colored people, I am now more prejudiced than I have ever been.” Later in the monologue, he said that “schools in University City are 40% integrated, when you have 40% you no longer have integration, you have a problem. What happened in University City is the result of some social do-gooders who felt that integration is a good thing.” He compared social do-gooders to college students who have their heads crammed full of all kinds of theories, but know nothing about the practicality of things. “Now these people have learned the hard way that it just doesn’t work. We refused to take a listing in University City and turned back another one just a few days ago. You just can’t expect to sell a house to a white family in that area.” He warned against trying to sell a house without the assistance of a real estate company because “your doorbell might ring, you open it and some big ‘buck nigger’ might stand there and want to see your house.” He related to the checker “we never break an area, i.e. we never sell to a ‘colored’ person unless there are already some ‘colored’ people living there. It would be bad business to do this. After all we must consider our reputation. We can usually screen our Negro voices on the telephone.” In response to the checker’s question what would they do if a black family wanted to buy her home, he replied: “we would not share your listing with them. In fact, we share only about one fifth of our listings with them. If they specifically asked for your house, we would have to show it because of the law.” He used this to illustrate how the federal government is running his business for him and is depriving him of his rights. He shared with this checker that he was then President of the Metropolitan St. Louis Real Estate Board. “In view of my prejudices I often have to talk out of both sides of my mouth and wear two hats as President of the Metropolitan Real Estate Board.”

A black checker visited Real Estate Company “B” for the purpose of purchasing a three bedroom home in the $22 – 25,000 price range or slightly higher. The checker was asked if she was interested in a specific area. The checker stated that she had no preference, that she was new in town and not familiar enough with the area to be able to indicate a preference. The agent gave her three listings in University City (integrated area) and one in Pasadena Hills (another area to which blacks are frequently referred to by realtors), and added, “That’s about all we have in your price range.”

About two weeks later the same black checker visited another branch office of the same real estate company, again for the purpose of purchasing a 3 bedroom house. This time she gave as her price range $24 – 28,000 – could stretch to $30,000. The agent told checker about two homes in University City (integrated area.) When the agent continued to show the checker University City listings, the checker indicated that she was from out of town, but had heard some unfavorable remarks about University City and was skeptical about the area. The agent told her: “I can’t imagine any difficulty in University City…Look at these homes. I’m sure you would like them and the area.”

A white checker visited the same two branch offices of Real Estate Company “B,” one of them on the same day as the black checker’s first visit, the other branch office one day earlier than the black checker’s first visit. In both instances the purpose of the checker’s visits was to purchase a 3 bedroom $18-22,000 house. The checker specified a geographical area of interest. Included in this area was University City, an integrated area, though not specifically mentioned by name.

In the white checker’s first visit the agent found only one house within the specified geographical area in a white area and then told checker he had nothing else. Homes in the white area are higher priced than checker indicated she could pay. Checker then asked if they listed homes all over. In response, agent said “yes.” Checker then asked how about something further east than Olivette (a white area.) The agent hesitated and when the checker questioned his hesitation, he replied:

“There are lots of colored in University City (this is adjacent to Olivette) and I want to be honest with you. Just like I don’t like to sell somebody a house with a flaw in it, I want you to know that, because I’m sure you wouldn’t want to live next to colored.” Later in the conversation the agent told the checker: “They, the colored, are moving into several areas, on Cadillac in Berkeley, Frostwood, Northwoods…..They put them in white areas where they want them to live. They, the NAACP, buy houses for them…..In the past we didn’t have to sell them a house unless there were three colored families on the block. That was the Real Estate Board’s law.”

In her second visit the following day to one of Real Estate Company “B’s” branch offices the checker was told by the agent that he had nothing in her price range in Olivette (a white area in specified geographical area.) “You would have to go to University City (integrated area) and that’s colored. You have to be real careful there.” Checker asked, “How come it’s all colored?” Agent: “It’s because they, the City (of University City) told the colored a few years ago they’re welcome there and they won’t be discriminated against and now it’s backfired on them. They’ve realized this and have started to do something about it. They no longer allow ‘for sale’ signs and they have an occupancy permit law. This occupancy law makes it real hard for the seller because he has to fix up his property, often to the tune of $2,000 or more before he can sell it. If he can’t afford it, he has to stay, or if he has to move, he has to sell at a loss.” The checker then asked him, “As an expert in the real estate business would you recommend a move to University City?” The agent’s reply was: ” I really wouldn’t, I don’t think you’d be happy there ….”

Ten days after this office visit, this checker received a telephone call from the above agent. He told her about a house in Olivette (a white area within specified geographical area.) He then added: “I got this listing from a friend, who is a real estate speculator. The house is his daughter’s and she is moving out of town. For fear colored will want to see it or buy it, there’ll be no ‘for sale’ sign up. This man (the speculator) is calling his friends in the real estate business and we’re all co-operating. The house is in a lovely neighborhood and there are no colored there.”

About four months later the same white checker visited the president of company “B” for the purpose of listing a house for sale. She told the president: “We want to sell our house. We are concerned about the neighborhood. I would like to discuss this with you.” His response was “I understand your concern. This is a tough world we live in. There is a law and it’s pretty hard to do anything about that. We have to watch ourselves too, because they are always checking us …. We’ll do all we can to help. One of the things you can do is not put a ‘for sale’ sign up in front of your house, this way they’ll never know that your house if for sale. We’d advertise in the paper, but there is always so much advertised in the paper that it’s hard to remember and figure out all the houses that are being sold ….. If they’d ask for your particular house we’d call you and then you could always use excuses for not being able to show it to them. You could say you’re going to be out of town, or that the time is not convenient, that you’re not going to be home then, and so on. By the time you run out of excuses, you hope they will have gone elsewhere.” After he ascertained where checker’s home was located he told checker: “You would not really have any problems, because your house would be more than the colored usually spend. They usually buy in the $13 – 18,000 bracket. If they buy more expensive homes, they have trouble getting a loan or making the monthly payments ….. The colored usually have to buy through FHA.” He added that his company “places many transfers of an international company located near your (checker’s) residence. Our salespeople always know the race of people this company refers to us. If they’re colored, we direct them to other areas.” Still later in the conversation, the president of Company “B” told the checker: “We’ve had white women come in to make arrangement to see a house and then they turn up with their husbands who are as big and as black as the ace of spades. I’m 59 years old. If I’m going to lose my hair or become grey, it’s because of those mixed marriages.”

All of the aforementioned describes some of the very blatant and overt methods of discrimination as practiced by members of the real estate community. Among the 15 real estate companies visited, we found one company whose discrimination methods are not always as blatant as those described before. The subtle nature can best be described by relating an actual situation of their discrimination methods. The family, the McC’s, were not checkers, but genuinely interested in renting a home.

IV. Actual Case History

On November 3, 1969, the McC.’s were shown a home for rent, owned by the F. family and listed with the B. Real Estate Company. After seeing the house they made application for it and left a deposit for two weeks rent with B. Real Estate Company. Since they did not hear from the B. Real Estate Company, Mrs. McC. phoned B. Real Estate Company and was told the house is not on the market anymore, because owner learned it was zoned commercially and wanted to rent it for commercial use. Later on the same day, Mrs. McC. picked up the money. On December 19, the day the McC. family was in contact with Freedom of Residence, this house was still empty.

On November 30, 1969, the McC.’s saw another house for rent by the B. Real Estate Company. They were shown this house, filled out an application for this house and left a deposit of two months’ rent, $270.00, with Mr. K., manager of one of the branch offices of B. Real Estate Company. The following day, December 1, Mr. K. told the McC.’s that he could not get in touch with the owner of the house, Mr. G., to determine how soon they could get in. Shortly thereafter the McC.’s were told that this owner had taken the house off the market because he wanted to redecorate, prior to renting the house.

On December 19 a Freedom of Residence staff member phoned Mr. G., owner of the second house and asked why he had refused to rent to the McC.’s. Mr. G.: “Because we need to make repairs and redecorate the house. We will list the house with B. Real Estate Company again when that is done – it’ll take us a while.” When Freedom of Residence staff member asked: “Where does that leave the McC.’s?” Mr. G. responded: “I don’t know.” Freedom of Residence staff person: “What did you tell B. Real Estate Company why you were not renting to McC.’s?” Mr. G.: “That the house was not tenable.” Freedom of Residence staff person: “The McC.’s have seen the house, know its condition and are willing to rent it as is. Why did you decide the house is not tenable after listing it with B. Real Estate Company?” Mr. G.: “I had not seen the house for one year and only saw what it looked like after listing it with B. Real Estate Company.” The Freedom of Residence staff person then shared with Mr. G. that it appears to the McC.’s as though they have been discriminated against. Mr. G. was also told that a Justice Department attorney had been in the Freedom of Residence office that day and we had discussed this situation with him and that he might be looking into it. Mr. G. was also told that Mr. McC. had indicated he wished to pursue the matter legally. Mr. G. replied: “Keep your shirt on. We’ll list house with B. Real Estate Company again after it’s redecorated.” When he was asked whether he would rent it to McC.’s then, he replied: “We’ll cross that bridge when we get there.”

On December 20, 1969, another white male checker phoned the office, expressing interest in the first house the McC.’s wanted to rent. He said he wanted to use it commercially. The checker was told that the property was leased. It could not be used commercially anyhow, because it was zoned residential.

On December 21, 1969 a Freedom of Residence staff person spoke to Mr. K., manager of the B. Real Estate Company branch office and asked him to explain what happened. Mr. K. related the following: “Shortly after the ‘for rent’ sign went up at the G. home (second house) the McC.’s came to their office. After they had seen the house, I drafted the lease in the absence of the listing agent. Then the owner, Mr. G., took the listing away from B. Real Estate Company because he wanted to redecorate house. I told him he might have trouble because the McC.’s are colored. They are nice quiet people, but they might sue since they are colored. They might get an injunction on house for one year and since this was to be investment property, that’s not what you want. (Mr. G. had bought this home from B. Real Estate Company about one year ago.) The McC.’s might be particularly suspicious since within the month a similar situation to them with another house.” The Freedom of Residence staff person asked him to explain what happened there. Mr. K.: “After that house was listed with B. Real Estate Company and after McC.’s had seen it and put down a deposit, the owner, Mr. F. called B. Real Estate Company to remove house from market. The owner said it is zoned commercial and they can get more money from it that way.”

On December 22, 1969 the master zoning plan was checked and it stated that the above house, owned by Mr. F. was zoned for multiple or single dwelling and shall never be zoned commercial.

On December 22, 1969 a Freedom of Residence staff person phoned another branch office of B. Real Estate Company and spoke to an agent, indicating that she wanted to rent her house and wanted to know how this was done. After some basic information was given, the Freedom of Residence staff person asked if and under what conditions a contract could be broken. The agent suggested that it would be best to ask Mr. L., manager of this office about this.

Later the Freedom of Residence staff person talked to Mr. L., manager of this branch of B. Real Estate Company. He too explained the basics first. When he was asked about breaking the contract, he referred to the federal law briefly and then added: “First of all we don’t advertise for quite a while, we pass the information around the office, and usually can find someone that way. Then you could specify if or when you want us to advertise.” When Mr. L. was asked what options were as far as refusing to rent, he replied, chuckling: “Just the other day we had a situation on property owned by someone who lives (and he mentioned area where Mr. G., owner of second home lives)…..The owner just said he wants to redecorate.” When Mr. L. was asked: “Wouldn’t we be bound by our contract with you?” his answer was: “We’d be willing to cancel your contract if it’s because of something like this, if it’s because of race.”

Still later the Freedom of Residence staff person phoned Mr. B., a high officer of B. Real Estate Company, relating all of the aforementioned information to him. He suggested that the staff person come in to meet with him and other officers of the company. He added that his company was not responsible for attitudes of their clients. It was pointed out to him that we were talking about an attitude suggested by Mr. L., manager.

About three hours later, a phone call was received from Mr. K., manager of one of the B. Real Estate Company branch offices. He said that Mr. G. (owner of second house) had changed his mind and would lease house to McC.’s, and would contract to do repairs with McC.’s in the house and therefore it would not be necessary to have a meeting. It should be noted that to date the McC.’s have not been told directly that they may lease the house.

On December 23, 1969 a meeting was held in B. Real Estate office as arranged the previous day. Present: Mr. B., Mr. L., and two other officers of B. Real Estate Company and two Freedom of Residence staff members.

Upon Mr. B.’s request a Freedom of Residence staff member related the entire situation by reading from case history.

One of the B. Real Estate Company officers went into a long explanation about the upkeep of rental property. Another officer stated that the McC.’s could rent the G. home, that Mr. G. had no objection to their renting it.

One Freedom of Residence staff person asked Mr. L. to explain the statement he made on the phone to her ….. “Just the other day we had a situation on property owned by someone who lives ….. The owner just said they want to redecorate.” Mr. L. said: “That’s a lie,” whereupon the other Freedom of Residence staff person got up and said: “That’s all, we’re leaving. We didn’t come here to be called liars. We’ll have to settle this in court.” Before we left we told Mr. B. that all the information has been shared with an attorney from the U.S. Department of Justice, and that he could expect to hear from him.

We predict that the subtle methods used in the McC. case (or similar subtle methods) will be used by real estate companies once the case has been prosecuted in court.

V. Application of Findings

A. Testimony at January 16, 1970 Hearings of U.S. Civil Rights Commission in St. Louis, Missouri

On January 16, 1970 a Freedom of Residence staff member testified at hearing of the U.S. Civil Rights Commission held in St. Louis, MO. Most of the aforementioned material was covered during this testimony. (Transcripts of the testimony can be obtained from the Civil Rights Commission.)

B. Disclosure of Findings to U.S. Department of Justice

All of the material uncovered in the “Patterns of Discrimination” project was presented to the U.S. Department of Justice on November 25, 1969. Since then some individual discrimination case material has been forwarded to the Justice Department. At that time Freedom of Residence requested that the Department of Justice file suit in the U.S. District Court, naming the fifteen (15) white real estate companies as defendants.

At the time of this writing we are still hoping that the Justice Department will prosecute and thus help put an end to practices such as evidenced in the aforementioned material.

VI. Results of Investigation

The findings of this investigation show that the result of this manipulation of the St. Louis, MO. housing market is to contain the black population in areas designated by white realtors. There is evidence indicating that the banks and other money lending institutions actively participate in this manipulation and the subsequent patterns that are developed.

The reasons for this containment will be the subjects of other reports. We list here, without comment those reasons we suspect to be valid. This list is not necessarily complete.

Reasons for containment of black population:

- To purposely deteriorate an area to induce Urban Renewal, Code Enforcement, etc.

- To induce real estate sales (“panic peddling , blockbusting, etc.”)

- As a result of a false “moral commitment” to “maintain the integrity” of communities.

VII. Conclusion – Author’s Note

We are well aware that this report does not have a customary conclusion. There are two reasons for this:

- To date no suit has been filed against the realtors.

- At the time of writing we see no end in sight for the discriminatory practices of the realtors.

VIII. Appendix Number 1

The following is a copy of a report on the activities of McDonnell-Douglas Corporation’s Housing Office. This report was mailed on February 6, 1970 to:

Secretary of Defense Melvin R. Laird with copies to:

- Senator Edward Kennedy

- Representative William Clay

- Mr. J. S. McDonnell

- Mr. Orrie Duerringer

Freedom of Residence operations began in 1961. Until Freedom of Residence was funded by the Danforth Foundation in May 1963, the organization operated financially on a shoestring and with the help of volunteers.

As a result of this, records were not always kept properly. However, in going through our files we found that from 1966 until the present time forty-three families, of which at least one member of the family was a McDonnell-Douglas Corporation employee, met with discrimination in their search for suitable housing.

To document this, we relate the following:

In 1964 McDonnell-Douglas Corporation hired a black man in their Data Processing Department. The family (wife and one child) came from out of town. The McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Housing Department gave him a list of housing located in Kinloch, Meecham Park (black enclaves) and black areas of the city of St. Louis. He had not indicated that this was his preference. A white friend, employed at McDonnell-Douglas Corporation, went to the Housing Department at that time and received a totally different list of housing in white areas. The black family eventually found suitable housing without the assistance of McDonnell-Douglas Corporation’s Housing Department.

After our office became aware of this, we called McDonnell-Douglas Corporation’s Housing Department, suggesting that Freedom of Residence might assist in finding housing for their black employees. We were told that no assistance was necessary. It was also denied that McDonnell-Douglas Corporation kept dual lists, one for white and another for black employees.

In May 1967 a recently returned Viet Nam veteran and his wife visited the Freedom of Residence office. He had just been hired by McDonnell-Douglas Corporation in their Production Department. He had been given a housing list by McDonnell-Douglas Corporation’s Housing Department, with housing suitable for himself and his wife, marked in red ink. All of the housing marked in red ink was in all black areas.

In March 1969 McDonnell-Douglas Corporation hired a single black man from another state as a Trainee/Technical Illustrator. Until he found suitable housing in mid-September 1969, almost six months later, he stayed at the YMCA. McDonnell-Douglas Corporation’s Housing Department provided him with a list of rental housing located both in the city and the county. He contacted many of the apartment complexes on this list, and also followed up on newspaper advertisements. Place after place advised him there was no vacancy. On several occasions he shared this with McDonnell-Douglas Corporation’s Housing Department, asking them for assistance. Repeatedly he was told that all they could do for him is give him an updated list and suggested that he keep on trying. Finally, early in September 1969, in utter despair, he went door to door, asking if an apartment is available, and found an apartment that was vacant and that he liked. When he called the real estate company who was leasing this unit, he was told the apartment was rented. A white checker from the Freedom of Residence office then phoned the real estate company and was told the apartment was available. The following morning the McDonnell-Douglas Corporation employee personally went to the real estate office to inquire about the apartment and again was told the apartment was rented. Five minutes later a white checker from Freedom of Residence entered the real estate office and asked about the same apartment and was told it was available. Two hours later another white checker from Freedom of Residence was told this same apartment was still available. When Freedom of Residence confronted the real estate company with all of this and shared with them that our client has indicated to us his intention to file suit to enforce his rights, the apartment became suddenly available to him. He has been living there since.

We cited this last situation in detail because it illustrates well what McDonnell-Douglas Corporation’s Housing Department could have and should have done. Had they intervened early, it would have prevented much frustration for one of their employees. It also would have shown some manner of “affirmative action” on the part of McDonnell-Douglas Corporation.

IX. Appendix Number 2

In the eighty-nine (89) visits made to the fifteen (15) white realtors the thirteen (13) black and white checkers found:

- 67 different methods and techniques of discriminating against blacks and

- 41 different methods and techniques of discriminating against whites.

Following are some of these methods and techniques. Others have also been included.

Discrimination Against Whites

1. By word.

A. “…You don’t want to live there, that’s colored…”

B.”…the property values are dropping…”

C. “…the schools are ‘bad’…” (meaning integrated)

D. “…crime rate is up, break-ins, etc….”

E. “…area deteriorated, blighted, unkept…”

F. “…integrated areas will be all black eventually…”

G. “…we’re (real estate company) not social pioneers…”

H. “…property in black and/or integrated areas is not a good investment…”

I. “…I (real estate agent) would recommend against purchasing in that (integrated) area…”

2. By lack of word – (Excluding black and/or integrated areas from the range of choices.)

A. Not offering listings of property in black and/or integrated areas.

B. Not noting positive aspects of integrated and/or black areas.

C. Assuming that whites should not or would not want to live in integrated and/or black areas.

3. By deed –

A. Refusal to accept listings in integrated and/or black areas.

B. Ignoring specific requests for listings in integrated areas.

C. Giving lists of specific areas to be avoided.

D. Lying about availability of property in integrated and/or black areas.

Discrimination Against Blacks

1. Ways of not showing and/or selling

A. “…seller is out of town…”

B. “…time is not convenient for seller…”

C. “…seller not at home…”

D. “We already have a contract on house.”

E. Pointing out only bad features of house.

F. The house is suddenly taken off the market.

G. Client discouraged from purchase because the unit is too far away.

H. Real estate company screens out “black” voices over the telephone.

I. Terms (price, loan, FHA, conventional, G.I., down payment, interest, etc.) keep changing so that no contract is ever accepted.

J. Real estate companies exert “sanctions” (will not share listings and/or customers, etc.) against companies cooperating with black clients.

K. Requiring unnecessary detailed financial disclosures.

L. Requiring financial qualifications higher than necessary.

M. Loan applications turned down in spite of qualifications. (False claims of “bad credit”, insufficient income, etc.)

N. Black buyer encouraged to make offer below minimum so that contract is rejected.

2. Attitudes and ignorance.

Generally speaking the black customer is often not offered the same courtesies as whites. In some cases black checkers were:

A. Not asked to be seated.

B. Were assumed to be “poor” and unable to meet financial qualifications.

C. Were not asked their names and/or other data.

D. Promised follow-up calls were not made.

E. Were offered less expensive and less desirable housing than that requested.

F. Assumed to need housing near bus lines (since most blacks are domestics.)

3. Inaccessibility to listings.

A. Blacks not made aware of some listings in white areas.

B. Blacks offered listings in integrated and/or black areas only, often despite repeated requests for listings in other areas.

C. Some listings in white areas are never made public…are passed around to other brokers who have agreed to share them with “select clientele,” the so-called “underground market…”

D. No “for sale” sign laws limit blacks’ accessibility because one method of finding houses, for sale signs, is eliminated.

E. Company policy declines listings from blacks and/or integrated areas.

F. Company policy is to tell blacks nothing is available.

G. Representative of real estate company will claim “nothing is available in that price range.”

H. One real estate company refers blacks to another company which handles property in black and/or integrated areas.

X. Settlement of the Case

The case was scheduled for trial in Federal Court in St. Louis on June 14, 1971. Just prior to that the U. S. Department of Justice entered into negotiations with the four real estate companies for a possible consent decree. After several months of negotiation, a fair housing agreement was negotiated and agreed to by the Justice Department and the four real estate companies on December 15, 1971. A separate agreement was also reached by the Justice Department and the Metropolitan St. Louis Real Estate Board. The Board consists of 509 member firms, 740 brokers and 3,300 sales personnel. This is the first time such an agreement has been reached between the Justice Department and a metropolitan real estate board. The agreement includes a new fair housing code which is to prevent blockbusting and steering. In addition, members are required to post fair housing notices in each office, state the fair housing policy on all residential listing contracts and inform their employees of their responsibilities under the code and the federal fair housing law. The Board must create an “Equal Rights Committee” (a self-policing body) to investigate allegations of discrimination in the sale or rental of housing. Upon request by the Justice Department, the Equal Rights Committee must inform the Justice Department of any information it has received concerning alleged violations of the fair housing code, including details of any investigations and transcripts of hearings held by the committee.

The four real estate companies against whom the suit had been filed must maintain records for three years, showing name, address, race, date and type of inquiry (rental or sale) made; address and date of transaction, if no transaction took place, state reason. The Justice Department has the right to inspect the records.

To summarize – An affirmative action program of compliance with the 1968 Fair Housing Act is to be effected by all realtors and associates of the Metropolitan St. Louis Real Estate Board within 60 days.

Note: The Greater St. Louis Committee for Freedom of Residence does not see this agreement as the end of discriminatory housing practices, but rather as a positive step in that direction. Our attitude to this code is one of “cautious optimism.” The next several months should put to a test what effects this code will have on alleged discriminatory housing practices.